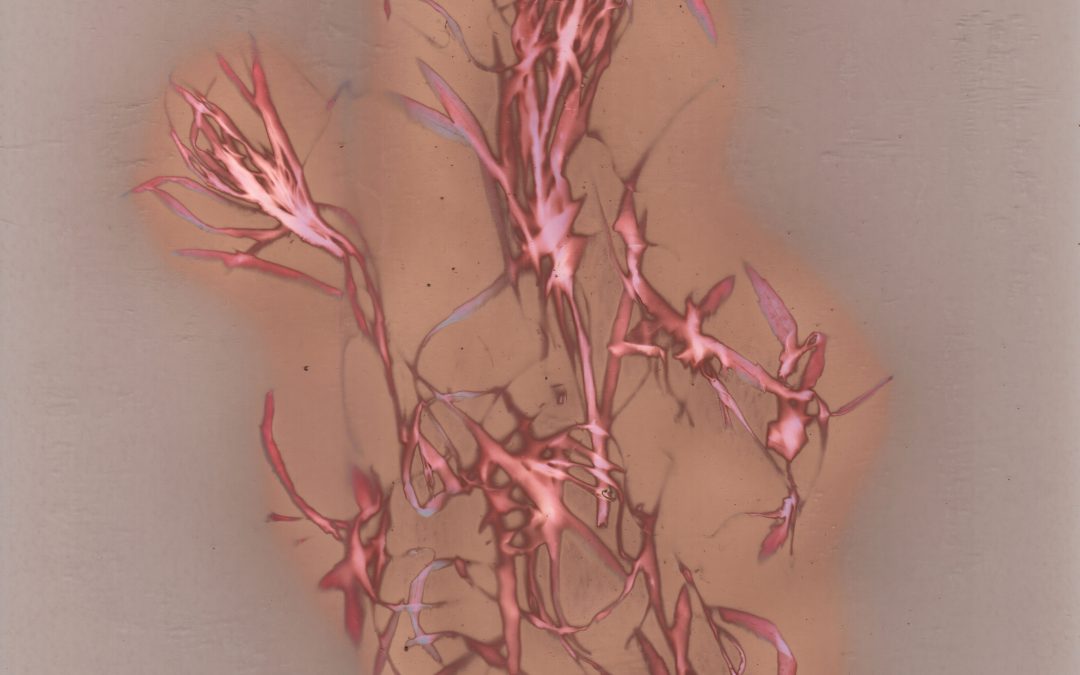

Image: Henry Wolff, from the series ‘Weōd’, 2024. Lumen print/Solar photogram. Image courtesy the artist.

Weōd

Henry Wolff

Exhibition dates:

23 February – 30 April 2024

Continuing research into the themes of care and connection, South Australian artist Henry Wolff presents works in response to their experience as Artist in Residence at leading Adelaide architecture and design practice, JPE Design Studio.

Exploring the sites JPE have been involved with has led Henry to collect and archive weeds, acknowledging them as markers for “spaces that are in a state of becoming and unbecoming, evolving and devolving.” Their works identify where care ends and pauses, using lumen prints/solar photograms to consider weeds for their formal qualities instead of their negative connotations.

The JPE Artist in Residence residency opportunity sees two artists a year take part in a creative exchange at JPE Design Studio, culminating in a work or installation presented during SALA and Fringe.

JPE Design Studio has been a place where emerging artists can exhibit, engage with studio culture and have an impact on design thinking since 2013. The JPE Artist in Residence program marks a new chapter of creative exchange in collaboration with Guildhouse.

A Semiotics of Weeds: On Henry Wolff’s Wēod

Wēod (pronounced as a single syllable with a gliding vowel, roughly, way-owd) is Old English for weed. Weeds are no delicate flowers. To be a good weed, a plant must be resilient, and grow and propagate readily in its environment. Being a weed is also to be where one shouldn’t. It is to be a plant out of place. It is to be permanently vulnerable – to be everywhere pulled up, poisoned or cut at the roots. So, what is a plant’s proper place? Plants themselves have no idea, they just grow as best they can wherever they find themselves. It is us who decide where plants should and shouldn’t grow, which is also to say, we decide which plants are weeds. There are all kinds of reasons for these decisions, but broadly, they are environmental, economic and aesthetic. Weeds earn their bad name by getting in places where their flourishing acts against these interests. Some, via the channels opened by colonialism and globalisation, find footholds in environments where they outcompete native plants. Some are poisonous – noxious weeds find their ways into environments where they threaten agriculture, livestock or people. Some weeds crowd out other plants that we find more desirable. Some are simply felt to be an ugly presence in the landscape, in our gardens and urban environments. Wherever they appear, they are also a sign that things have run out of control, that a culture that seeks to protect the environment, agriculture, and orderly life in suburbs and cities, is failing.

The photographs in Henry Wolff’s series Wēod are images of weeds, and most of them are lumen prints, the product of a kind of cameraless photography. Lumen prints are made by placing an object directly on black and white photographic paper and exposing it to the sun. The lumen prints in Wēod show the distinctive soft coloration typical of the process, delicate greys, blues and pinks. These evocative colours are features of the photochemical reactions on the paper, unrelated to the colours of the subject matter. Some of the silhouetted shapes of leaves and stems are easily understood. Other elements require some knowledge of the process to understand. These include the brown auras around some of the plants, where their moisture has reacted with the silver halide, and the bright areas which register the overlapping of leaves.

Wolff is keenly sensitive to the metaphorical potential of weeds. By their nature, weeds are apt symbols for people marginalised by the dominant culture. Wolff’s weeds are incomplete plants, torn off at the roots, a reminder of the vulnerability of those who do not fit in. The Old English word wēod reminds us that weeds have been disturbing Western civilization for a very long time. In this way too, they are excellent symbols of marginalised communities, that are likewise permanently, it seems, at risk, and yet tenacious despite that. Wolff has earlier made work around the theme of care, documenting and enacting forms of interpersonal and personal care involving their friends, family and Wolff themself in conversation and performance.[1] Wēod can also be understood as a reflection on care. For Wolff, weeds are an especially appropriate metaphor for queer people and queer communities. Finding beauty in these plants is a way of symbolically asserting the intrinsic value of those of us who do not fit accepted categories. Indeed, Wolff presents his weeds not as othered, despised things, but simply as plants, isolated and transfigured by the lumen printing process. In this way, we can see them not as plants out of place, but simply plants as they are, appreciating them for their own intrinsic qualities. Perhaps the point is an obvious one, but that is a skill we have a duty to bring to bear in our relations with people and communities too.

Michael Newall, February 2024

Michael Newall is a writer on art and a philosopher. With Eleen Deprez, he directs The Little Machine: A Space for Contemporary and Experimental Art, in Regent Arcade, Adelaide. He is also an Adjunct Research Fellow at the University of South Australia.

[1] Eleen M. Deprez and Michael Newall, ‘Henry Wolff’s CARE’, Fine Print, pause-play project, 2021. www.fineprintmagazine.com/projects/henry-wolffs-care-by-eleen-m-deprez-michael-newall

Image: Henry Wolff, photograph Sia Duff.

Henry Wolff

Fringe 2024

Henry Wolff’s practice is concerned with images that articulate vulnerability in their participation with the world/s of their collaborators. With an empathetic observational methodology, they produce moving image, photographic, and performance works that attend to the power of marginality and diffraction within society. Through attention to human connection, they explore entangled experiences of being, and foster the moral virtues of compassion, care, and love.

Recently Henry has been commissioned by Photo Australia for PHOTO 2022; They are a feature artist for 2022 Gertrude Street Projection Festival; They exhibited in the 2022 Melbourne Art Fair, ‘Precinct Night’ at Collingwood yards; They performed at AGSA with APHIDS for the 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art; Their work ‘Sibling’ was identified as one of the 125 most exciting artworks from around the world by Aesthetica Art Magazine (UK).

Henry is mentored by Hoda Afshar, Eugenia Lim (2019-present), & Amos Gebhardt, David Rosetzky (2021-2022) through the support of the Centre for Projection Art.