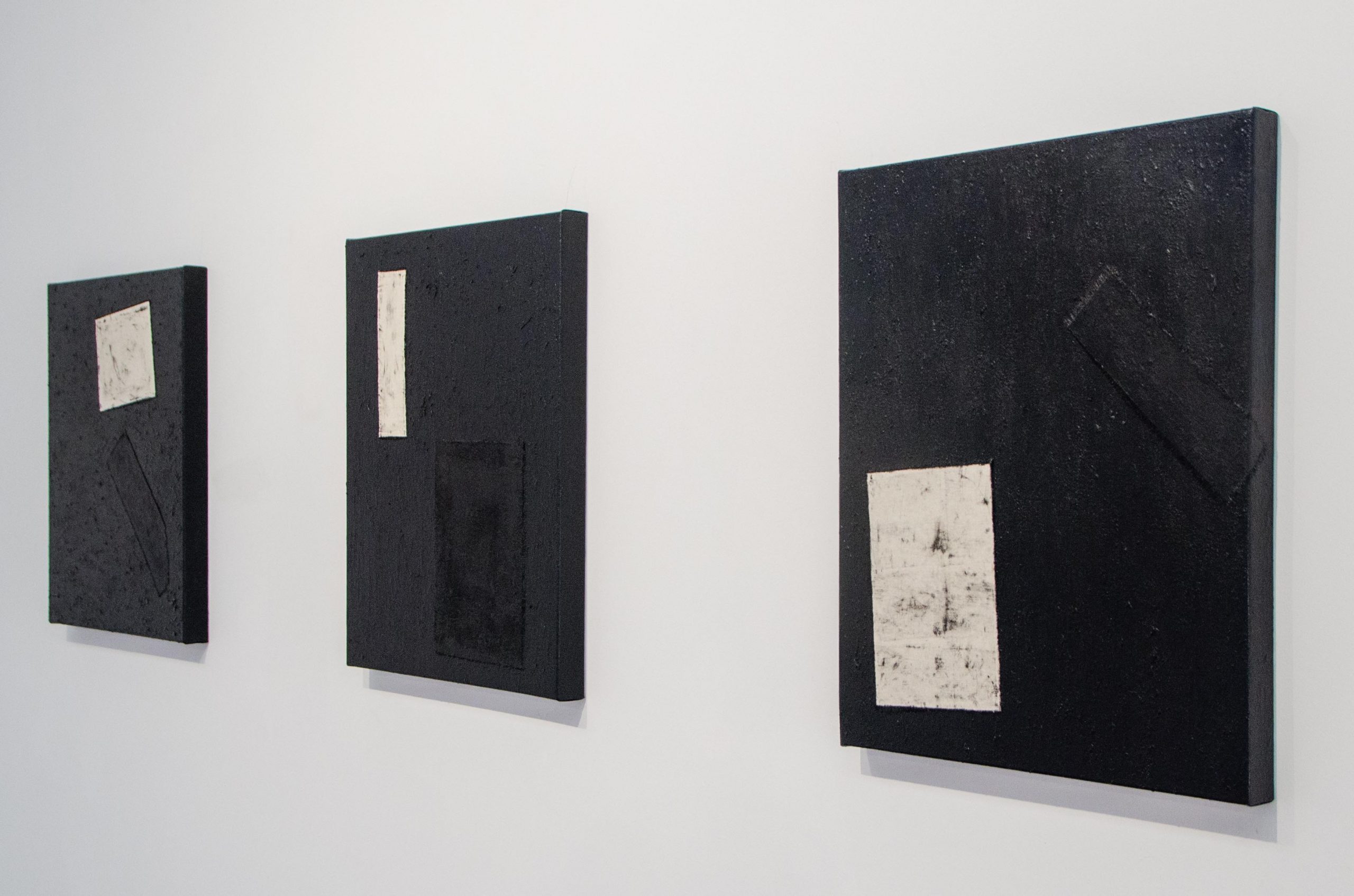

Image: S P A C E S (installation view), 2020. Photograph: Sam Roberts.

Born in South Korea, Jonathan Kim is now based in Adelaide, South Australia. His multidisciplinary practice places deep importance on the relationship between a medium and its environmental factors, a concept named ‘Gong-Gan-Seong (Spatiality)’, inspired by Lee Ufan’s philosophy of ‘Man-Nam (Encounter)’. Kim’s work ‘Calico & Gesso on Canvas Series’ (2020) is included in S P A C E S, an exhibition that explores the way we navigate through and experience our surroundings. In this interview with curator Steph Cibich, Kim discusses the artwork and the driving force behind his practice.

S P A C E S is presented as part of the ART WORKS 2020 Emerging Curator Program, delivered by Guildhouse in partnership with the City of Adelaide.

How would you describe your practice?

Over the years, my art practice has built and expanded my own concept of Gong-Gan-Seong (Spatiality). My early work was inspired by Korean artist Lee Ufan’s theory ‘Encounter’, which focused on the relationship between things. In Lee’s concept, relationships are formed by the interaction of subject and object, and it becomes structural work even though the phenomenon itself is invisible. This phenomenological structure, called Gong-Gan-Seong in my research, is continuous, variable, and arbitrary. Interaction is a continuous phenomenon, not a static scene. It is also influenced by many surrounding factors such as light, temperature, weather, or audience.

The ‘Encounter’ theory explains that for the audience to recognise interactions or relationships, all senses of the body should be used for an impromptu perceptual experience without prejudice or stereotypes. This is because memory, prejudice or bias, interferes with access to the nature of interactions and distorts perceptual experiences. This spatial relationship is physical, not conceptual, and should be detected by the body, not by the brain.

Over the past two years, I have been expanding my Gong-Gan-Seong by applying various post-minimal ideas to my artistic concepts. At the same time, the East Asian structuralism has been reflected in my practice through East Asian ideas, such as the Taoism, Yin Yang, and Feng Shui. Especially, I am trying to incorporate the concept of self (自) and other (他) into Western art.

Can you briefly describe your work ‘Calico & Gesso on Canvas Series’ (2020), featured in this exhibition and the ideas that led you to make it?

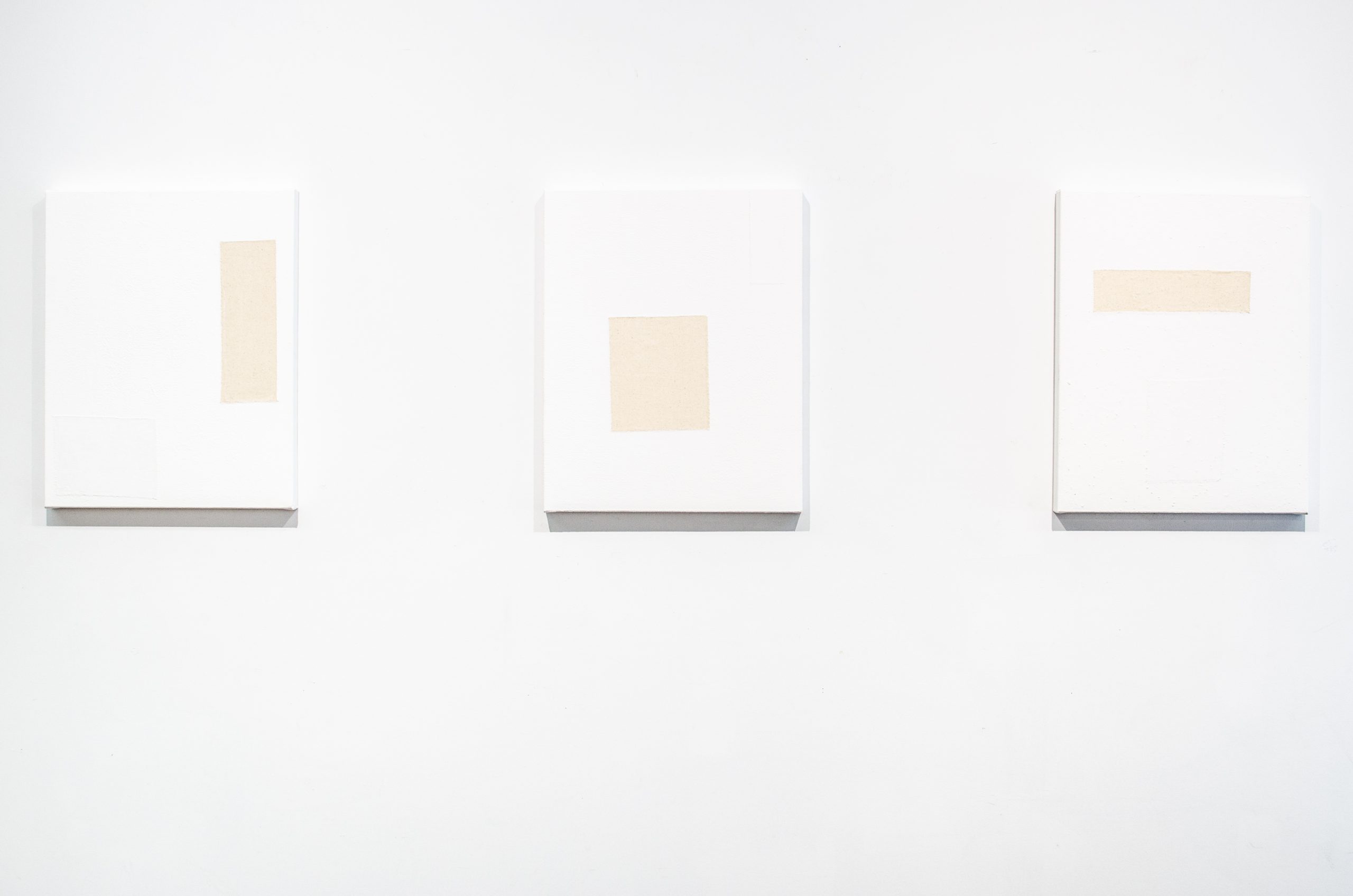

Calico & Gesso on Canvas Series is a follow-up to The White Series, which I produced at the British School in Rome last year (2019). The White Series emphasises the texture of the paper with the density difference between crayons and ink. It is in line with the Korean painting style Dansaekhwa in that it applied Obangsaek (Five Colours Five Directions), the traditional colour theory of Korea. The part left in white was inspired by the structure of Rome, but its ambiguity asks questions about which parts of the picture are positive and which are negative.

In the Calico & Gesso on Canvas Series, I painted over the canvas more than 30 times to create the texture of the medium. Also, the black and white symbolise Yin and Yang to follow the context of Dansaekhwa. The calico pieces are similar to canvas materials which makes the audience ask what the subject of the painting is.

Images: Jonathan Kim, Calico & Gesso on Canvas Series, 2020. Photograph courtesy the artist.

Your work is usually underpinned by sculptural elements. How does this set of canvases connect or differ from your other works?

I have been working hard on sculpture after my residency in Rome. So, many people know me only as a sculptor or an installation artist. However, as I mentioned earlier, painting is not only a significant part of my existing research, but it is also a method that creates Gong-Gan-Seong in my practice.

Lee Ufan’s philosophy not only became the root of the Japanese sculpture movement, Mono-ha, but also greatly influenced the Korean painting style Dansaekhwa. Dansaekhwa is interpreted as Monochrome Painting when translated directly into English, but actually, the term of monochrome is not crucial in Dansaekhwa. Rather, Dansaekhwa places importance on the unique tactile nature of the media that make up the painting, which is created by the inherent nature of the material and the intervention of the artist. On the other hand, history and memory contained in the media are other vital elements of the concept of Dansaekhwa.

Each piece of this Calico and Gesso on Canvas series looks similar, but the textures of multiple overpainted gesso and the composition created by pieces of calico reflect the artist’s movements and environmental factors at the time of work as Gong-Gan-Seong. Therefore, I want the audience to detect the Gong-Gan-Seong of each work through their bodies without any information. Perhaps more people would prefer to understand this work through the information provided, but those are just structures to create Gong-Gan-Seong.

Much of your practice investigates ‘Spatiality’ and the relationship between an object and its environment. What made you want to explore these ideas?

In fact, my early art practice pursued minimalism. I wanted to explore the nature of the material and present it to the audience. However, in the Mirror and Plaster Series that was installed in my Bachelor’s graduation exhibition, I found that other environmental factors beside the materials of mirrors and plaster were also involved in the work. I started to study this phenomenon in my Honour’s program the following year.

A year of academic research was related to Japanese Mono-ha and Korean Dansaekhwa, which were not only contemporaneous with post-minimal movements but also based on the artistic concepts of Korean artist Lee Ufan. Since then, I have discovered my concept of Gong-Gan-Seong, and I am currently expanding and re-discovering the new meaning of Spatiality by studying other post-minimalist art movements. I believe that Gong-Gan-Seong not only shows the true value of media but also restores people’s sense of balance by providing a spatial experience based on the claims of a communication theorist Marshall McLuhan.

When we discussed your work in the exhibition, there was no specific order for the canvases. What impact does placement have on the energy and interpretation of your work, especially when it is installed by another person?

My work is often installed by others, unavoidably. In particular, working with Korean artists during COVID-19, I am facing a situation in which another artist has to create and install my work instead of me. In my practice, interaction and interrelation are very important key elements, and the body is an instrument that detects them, so I am very careful about installing my work where my body is not located. I believe the person in the site can sense the material and space through the body and better reflect the nature of the space. Of course, errors created by the intervention of the installer are inevitable. I take it as a part of my practice because I regard the balance created in the space are more important than maintaining the original work.

How do you think ‘Calico & Gesso on Canvas Series’ (2020) speaks to other artworks in the exhibition? Are there any clashes or connections?

I was honestly concerned about the scale of the paintings before they were installed in Adelaide Town Hall. I was also very curious about how the exhibition space with the European interior would be in balance with my paintings reflecting East Asian ideas. But when I checked the final installation, the size and design of the rooms interior did not alter the context of the work.

The concept of my practice, Gong-Gan-Seong, is related to the interrelationship between the subject and the object. I think my paintings, along with other artworks, are creating a balance of relations in some way in the exhibition space. The interaction may be positive or negative in an objective view but interpreting it as harmony and conflict is a very subjective point of view. This exhibition, titled S P A C E S is the result of all the previous happenings in this exhibition space, and it is already a balanced unity in itself. The only variable is just the subjective observation of the audience re-discovering and re-perceiving it.

The exhibition is titled S P A C E S and explores the way we navigate through and experience our surroundings. How have your experiences of ‘space’ been affected by COVID-19? Has this created a different energy in your investigation of ‘Spatiality’?

2020 has been an exceptionally challenging year. The long shadow of COVID-19 has affected every aspect of our lives, not to mention the devastation of Australia’s bushfires, the ongoing climate crisis and the significance of Black Lives Matter. What role does art have for individuals and for our communities during these challenging times?

These two questions are closely related to my current projects for next year, so I want to answer all at once.

Recently, my work has put a lot of effort into reflecting the meaning of the subject (self, 自) and object (other, 他) based on East Asian philosophy in Western art. Meanwhile, a few months ago, I received the theme of 門(Door) from a Korean choreographer Sun-young Lee, and planned the current projects to respond to COVID-19.

Door(門) is a passage that links the two separate spaces, but the opened-door and closed-door have opposing meanings of connection and disconnection. However, there is a letter 們 in homonym, which is a suffix that changes nouns or pronouns that refer to person into plural forms. In other words, when 們 is attached to 我(I), it becomes 我們(we). However, the letter 們(人+門) looks like a person standing in front of the door, which gives me a new message.

There is a door between the self and the others, and it can be closed or opened. The self is singular and the others are plural. Once going through the open door, the self must disappear and become the others. Therefore, it is a coexistence that self becomes others, and the beginning is to open the door.

Through my projects, I will open the doors to connect the two separated spaces in this pandemic era through digital technology. However, I hope these small happenings done by artists from both countries, Australia and South Korea, will serve as an opportunity to rethink global coexistence, including environmental issues, not just in a message reflecting this COVID-19.

Jonathan Kim

Kim’s practice places a deep importance on the relationship between a medium and its environmental factors. This concept is named ‘Gong-Gan-Seong (Spatiality)’ and was inspired by Lee Ufan’s philosophy of ‘Man-Nam (Encounter)’ that was contemporaneous with the Post-minimalist art movement of the 1970s. This concept is fundamental to Kim’s research into Phenomenology and his ongoing practice which explores the physical properties of a material or object and the various spatial tensions formed by them. The meaning of Kim’s ‘Spatiality’ continues to expand and evolve, embracing other post-minimal concepts and the ways in which a relationship between a thing and its surroundings is more important than its physical work.

Born in South Korea, Kim is now based in Adelaide, South Australia. His multidisciplinary practice encompasses painting, sculpture and mixed media installation. His works frequently reference traditional Korean design and painting styles, post-minimalist concepts as well as the sculptural theories of the Japanese Mono-ha artists. Kim graduated with a Bachelor of Visual Art (Sculpture) in 2017 and Honours (2018) before undertaking the Helpmann Academy’s British School at Rome Residency. His work has been exhibited at the esteemed national graduate exhibition ‘Hatched’ at PICA (Perth Institute of Contemporary Art) and the Helpmann Academy Graduate exhibition (2019). Recently, Kim has participated in solo and group exhibitions at West Gallery Thebarton, Sydney Contemporary, the Korean Cultural Centre (NSW), Sauerbier House, FELTspace Gallery, Linden New Art and Praxis ARTSPACE.